Subject to Change

I remember being a young film student. I was a cocktail similar to my art student contemporaries; 1 part enthusiasm, 1 part naïveté, stir well and add a dash of disillusionment, any flavor of bitter will do. As a student, a professor told my class, “no matter the state of the world and its economy, the industry of moving image will prevail.” Since then, I’ve always looked to film for answers. It was in moving images where I discovered many parts of myself that were hidden from my waking life. It was within cinema where I learned the many complexities of being.

Cinema was almost like a secret pictorial language, and by watching I learned to read and speak a hidden dialect. Just as spoken language relies on the percussion of our vocal cords and the dance of lip and tongue to provide the emphasis and cadence necessary to mouth a word, the language of cinema relies on the body. One thing I know to be true of all language is its adaptive nature and inherent mutability. For cinema, and all moving image works in the lineage of cinema, change is not a threat but a promise of vitality and relevance.

In this moment, when the world shelters in place, where we are unable to gather in the beloved arrangement of seats in a dark theatre or huddle at the edge of a projection box in a museum, I’m excited by the notion that our visual perception will inevitably adapt. The legibility of detail and color will transmogrify and force us to reassess our aesthetic values and how those values connect to our inner and outer worlds.

“Skin has become inadequate in interfacing with reality. Technology has become the body’s new membrane of existence.”

– Nam June Paik

There exists, in this moment of transition, a potential to explore the possibilities of our sensorial experiences through digital interfaces. We can redefine touch, taste, sight, smell, sound. We can create past the primary senses and move into thinking about our more complex, neurological sense preceptors, as they can be translated into digital content.

A future of the cinematographic arts, or at least the most exciting version of its potential future, has been written and almost packaged as an instructional. In “In Defense of the Poor Image” (2009), Hito Steyerl lays out a world where images are at once communist and capitalist, where trash is treasure, and the idea of an “original” struggles to find fidelity in digitalia. Steyerl writes, “The circulation of poor images feeds into both capitalist media assembly lines and alternative audiovisual economies. In addition to a lot of confusion and stupefaction, it also possibly creates disruptive movements of thought and affect.”

There exists, in this moment of transition, a potential to explore the possibilities of our sensorial experiences through digital interfaces. We can redefine touch, taste, sight, smell, sound. We can create past the primary senses and move into thinking about our more complex, neurological sense preceptors, as they can be translated into digital content.

A future of the cinematographic arts, or at least the most exciting version of its potential future, has been written and almost packaged as an instructional. In “Defense of the Poor Image” (2009), Hito Steyerl lays out a world where images are at once communist and capitalist, where trash is treasure, and the idea of an “original” struggles to find fidelity in digitalia. Steyerl writes, “The circulation of poor images feeds into both capitalist media assembly lines and alternative audiovisual economies. In addition to a lot of confusion and stupefaction, it also possibly creates disruptive movements of thought and affect.”

In an idealized version of the cinematic future, video art, experimental and independent film works will assert importance and hopefully claim dominance as we witness the dissolution of mainstream content. As film companies close internationally and galleries and museums penny-pinch, we won’t be beholden to an industry structure. In a 2010 interview with John L. Jackson Jr., Haile Gerima described a dangerous and misleading tradition of cinema that, “monopolistically imposes itself on people as a kind of complete reality and can sometimes replace a person’s original and intuitive knowledge and temperament. It displaces those sensibilities. It makes its own standard the official standard. You are taught to believe that cinematic stories can only be told in certain ways about certain validated subjects.” Merge his ambition to combat this tradition anddecolonize the filmic mindwith Steyerl’s vision of a distribution current that proliferates thepoor imageand we have the skeleton of a cinematic future.

In Jillian Crochet’s work, she negotiates the translation of a tactile world on a digital interface. Crochet begins her dictation of the video future in ,It’s ok.(2020), tracing the prickly edges of an aloe plant with her fingertips. The remaining videos of the triptych, It’s ok. (gloved) and It’s ok. (screen), transitions to the unsatisfying reality of having to trace the memory of a sensation, with Crochet tracing the same plant with a gloved hand, and then tracing an image of the plant on a screen. Her work, Does this feel normal? (2018), takes us further into questioning our new tactile realities as we watch a forced and uncomfortable impact between a hammer and a rock. The truth is it does not feel normal because in this moment we can only imagine the feeling of receiving impact from another body.

Maxine Schoefer-Wulf explores the celluloid process—in an irregular film fetish fashion —through over-processing and painting 16mm film stock with watercolor and beach water then abstracting it twice over through digital removal. Ironically, all this processing does is bring you back to the material grit of film stock, somehow successfully transporting you to the edge of an ocean’s crashing tides. Schoefer-Wulf reminds you in the cacophony of wind and water, that there still exists a gravitational pull of the sun and moon on the largest body on earth.

Jeff Enlow disregards tradition and submits to the vertical reality of our image-making devices. His vimeo presentation is contorted to an aspect ratio of 9:16 to reveal an almost too distant image of a video monitor, in its expected orientation, playing what appears to be a poorly composed home movie. He’s reproduced this image in the spirit of irreverence of the original document. Enlow’s title of the work,The Myth of Apollo, wields the hubris of ancient Greek mythology to escort you into his future-facing dark sense of humor.

If this is a peek into the future of video, CCA’s MFA graduates have their ear to the ground or more appropriately their eyes on the screen. They are, at the very least, trying to locate themselves in a digital future from within the mechanics of poor image production.

“Making is a matter of finding the grain of the world’s becoming and following its course.”

Tim Ingold, The Textility of Making

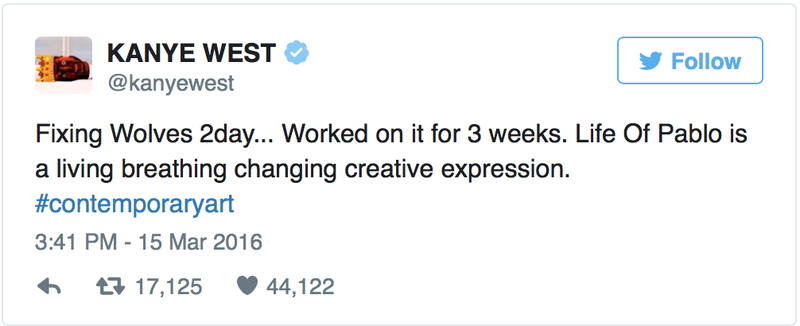

Remember The Life of Pablo? It was Kanye’s last real rap album that most everyone could still get behind without feeling guilty. One thing I’m thankful for in this moment of shelter in place is the ample time and space to reacquaint myself with the practice of listening to old albums from top to bottom. The Life of Pablo was top of the queue for one of my solo listening parties, and upon listening I was quickly reminded of the album’s polarizing release in February of 2016. I was about to graduate from the MFA program at Mills College and believe it or not, I was still burning albums to CDs, and that was mostly how I listened to that particular album. Yes, I had a functioning CD player. The Life of Pablo was my last real CD album experience. Thirteen tracks in, as I was listening toWolves, I remembered the controversy Kanye created after changing several tracks on the album after the original release. It was unprecedented for an artist to make major alterations to the production of an album, after it had already been published on streaming sites and everyone had spent time, almost two months, memorizing each track.

Is it a stretch to wonder if Kanye read Steyerl’s vision? Not to give Kanye any more credit than he already gives himself, but the level of authorship displayed in The Life of Pablo, and defiance of the music corporation’s expectations, gave permission to other content producers to do with our content whatever they pleased and whenever. The permission to not be myopic. Just as Kanye changes his album content at the whim of his own imagination, digital content is not a static object. Videos can exist in versions. You can create, upload, delete, re-edit, and upload again as an abridged work. No pressure to notify the public or ask permission. The gallery, the theatre, the museum, is not live. The venue is now a link, a download, a digital document and it is always subject to change.

“The poor image […] is about its own real conditions of existence: about swarm circulation, digital dispersion, fractured and flexible temporalities. It is about defiance and appropriation just as it is about conformism and exploitation.

In short: it is about reality.”

–Hito Steyerl, In Defense of the Poor Image

Leila Weefur (She/They/He) is a trans-gender-noncomforming artist, writer, and curator based in Oakland, CA. Through video and installation they examine the performativity intrinsic to systems of belonging present in our lived experiences. The work brings together concepts of the sensorial memory, abject Blackness, hyper surveillance, and the erotic. Weefur is a recipient of the Hung Liu award, the Murphy & Cadogan award, and the Walter & Elise Haas Creative Work Fund. Weefur has worked with local and national institutions including SFMOMA, CCA’s The Wattis Institute, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, and Smack Mellon in Brooklyn, New York. Weefur is a lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley, and a member of The Black Aesthetic.