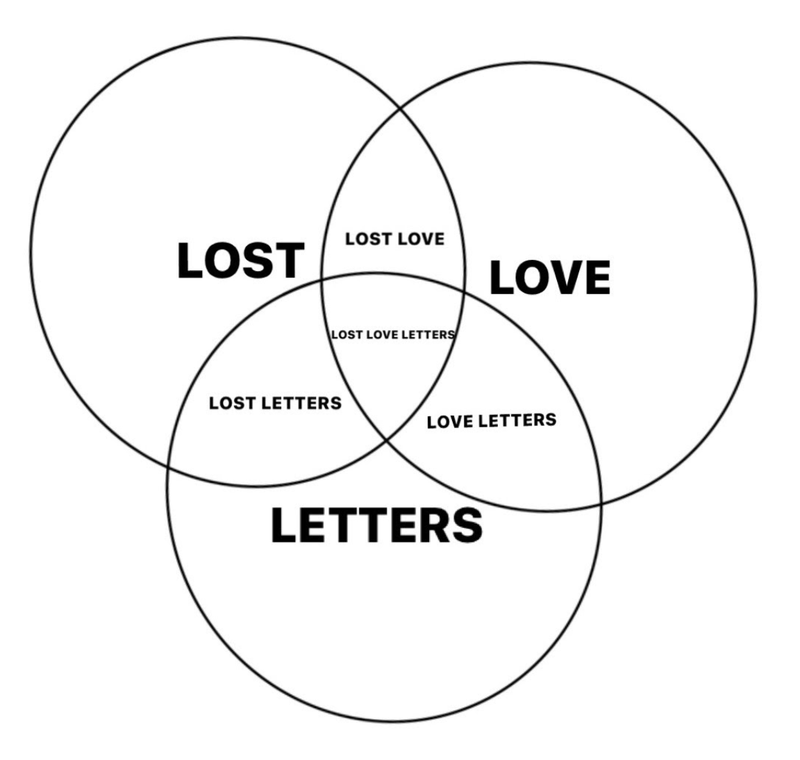

Lost, Love, Letters: Selected Creative Writing by Christine Lyon

Lost Dove, or Looking for Myself in Wikipedia Articles on Extinct Birds

“Carolina parakeets are the only parrot species endemic to the U.S. that went extinct because they were too loyal to each other.”

The last captive parakeet died February 21, 1918 in the same cage as Martha, the last passenger pigeon, who died four years earlier.

There are no scientific studies or surveys of this bird by American naturalists; most information about it is from anecdotal accounts and museum specimens. Details of its prevalence and decline are unverified, or speculative.

“About 720 skins and 16 skeletons are housed in museums around the world and analyzable DNA has been extracted from them.”

A factor that exacerbated their decline to extinction was the flocking behavior that led them to return to the vicinity of dead and dying birds, enabling wholesale slaughter. I, too, often return to the scene of the crime to make sense of it all only to get hurt. I come from a lineage that flocks to tragedy, ghosts, and prey.

The Carolina parakeet was declared extinct in 1939. Martha the passenger pigeon, her cellmate, was often confused for a mourning dove. Her name is derived from the French word “passages,” meaning “passing by,” fleeting, wandering. In Choctaw, they called her the “lost dove.”

“Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus coined the binomial name Columba macroura for both the mourning dove and the passenger pigeon in the 1758 edition of his work Systema Naturae (the starting point of biological nomenclature), wherein he appears to have considered the two identical.”

There is nothing to suggest Linnaeus ever saw specimens of these birds himself. His description is thought to be fully derivative of these earlier accounts and their illustrations.

I did not bother to read his descriptions of these birds. They were myths anyway, along with a wedge-shaped tail/tale, spun by men who warm themselves by wood-burning stoves, who loved the sound of their own voice so much they painted the sound, and gave it a big, boastful, gleaming name, a name that campaigns for itself like “American Progress,” or something. The birds are re-imagined and bemoaned, offered up to be mythologized again and again, a game of telephone spanning centuries and through the revolving door of development, destabilization, and deforestation. I do not need to look at their illustrations to understand that their bird bones were fragile, I am too. I am not a biologist, I am a narcissist. I am interested in incorporating the Passenger pigeon and Carolina parakeet into my own myth, to understand myself, and my fragility, maybe become a social bird, too, before I perish; caged, forgotten, mythicized, having once been so fruitful and multiplied.

Embracing my vertigo, I am intrigued by all that which once reached a great peak only to fall. An essential part of the fear of falling is the siren song of the ground below. I have had many dreams of my epitaph, my myth which will be more loved, more certain, more desired, than the fog of actually existing. And yet I am haunted by my double, my would-be ghost, who passes by me, and whispers in my ear, taunting, “you are too afraid to truly love.”

Will We Make A Sound?

When people talk, they hardly move their upper lips to form sounds—taking care with the wrong words, quivering gently around wrong vowels.

Sometimes when I ask stupid questions, I feel my bottom lip flip and flap against swollen gums.

After school, unpeeling in the quiet, I see our neighbors. Twin brothers, wearing matching slacks, riding their bikes around the block. A pair of pamphlet pushers full of bad good news: big promises and rules. I pretend we aren’t home.

The instinct to hate yourself is right. You and I are two square pegs left out of holes. Everything is the same shape, and nothing is strange enough to care about.

Lonely, in a small vapid space, we decide to rob them all. Masked up, Friday the 13th and “try whatever you want, dude,” calling up the young boys to slide through with pistols. But they’re faded, playing video games.

Fly the mothership toward the other side; I heard it was greener. The nights are made of street lamps here, numb to the trees and stars.

Milk, or Swimming Through WebMD’s Advice on Relationships & Calcium Deficiency

Symptoms:

There are no vitamins here. None of your words were your own. They had no nutrients and made a mess: divided into several halves, one of which has yet to be found somewhere here, crumbling in the bottom of this glass of milk. I refuse to drink it this far past the morning, and should be tamed by now.

Causes:

You were so porcelain: so bland and sweet, daisy yellow dairy and chaff so eager to kiss. Blood clotting, your sweat still on my quilt: the siren that drowned me, leaving my body among young sailor bones, longing and rotting in the marrow.

Treatment:

Malnourished, I keep returning to the sea, brittle and broken. My teeth stink, and I can’t sleep. All these listless nights peeling back pale mermaid scales like onion skins. Nothing cured.

Overcoming Past Madness & Learning to Love the Truth

Once, with one pale blue eye, you looked at me. The other eye was, and I suppose, still is, green. It pulled away, and took the blue eye along with it. I swore I was gleaming in your peripheral, but I wasn’t and that had to be fine.

Your pupils were sad, soft, and underground; somewhere passed the descent toward SFO, where the plane hovers above the bay, and you swear the water could swallow you whole.

When you land on the tarmac, your mind is ahead of you, already paying the toll, northbound on 101, off to somewhere else: somewhere sweet, beautiful, brunette, and quiet.

Paint Me Like One of Your French Girls (That Sinking Feeling)

When I was six, Jessie was fourteen, and she had seen Titanic fifteen times. I don’t know how I know that or who told me. Memories from that age are slippery, just as they are for most people, I imagine. I know I didn’t understand death yet. Our grandma died when I was three, which means Jessie would have been eleven. She probably understood death more than a three-year-old could, but looking back now and knowing what it was like to be a preteen, I have my doubts about how much she could really conceptualize it, though her time in the hospital may have made it clearer. I didn’t understand what was lost when our grandma died. I didn’t understand the sadness and destruction left behind. She went away in her sleep. It seemed natural. I was either shielded from, or I do not remember, the grief. I knew she meant a lot to our family. I remember that she brought a lot of laughter and joy with her. So much of our family’s faith in medicinal properties of humor can be traced back to her.

When Jesse was younger, about two years old, she had leukemia. While in the hospital, the family had to keep her visitors to a minimum because of her weakened immune system. My grandpa saw it as a personal affront that his girlfriend/student, Darlene, was not on that short list of people. (I don’t know if Darlene was actually his student, but it’s not necessarily untrue to tell the story that way. My grandpa was a Drama professor at the University of Oregon who since, and probably before, his divorce, had been through a slew of flings with his students. So it’s not unimaginable that Darlene was one of these students.) He refused to see Jessie in a huff. In response, my Grandma picked up some pom poms that one of Jessie’s sisters must have brought with her, and proceeded to perform a “Give My Regards To Darlene” routine to the tune of “Give My Regards To Broadway.” I wasn’t there, but it’s one of those stories that’s a part of our familial lore, told and retold on holidays.

At six, I was with my mother and her sister visiting my paternal grandmother in Salinas, California. For some reason, I remember that we were in the kitchen laughing. It was something about the false bottom styrofoam cups that our Jamba Juice smoothies came in. I don’t know if it was the punchline or the set up or if it was a joke at all, but I remember there was something about it that was making us laugh when the phone rang. I remember our laughter stopping short, feeling suddenly inappropriate. The voice on the other end of the line, I don’t remember whose, told my aunt to come home immediately, that Jessie committed to her romantic attachment to death: a Cronenbergian amalgamation of the tragedy of Jack and Rose and the Christian promise of an afterlife in paradise. We found out that she and her boyfriend made a pact to kill themselves. Her boyfriend didn’t do it but she did, while her drunk father negligently watched over her and her four sisters. (Some people think there was room on that floating debris for both Jack and Rose. I have my doubts. Jack was created to die.)

The chemotherapy she had undergone so early in her development caused problems that interfered with her ability to learn. Her father would repeatedly berate her for her “stupidity.” He’s dead now too, and I still don’t forgive him.

I learned at a young age that no matter what happens, no matter how much I wanted to die, I needed to stay alive for my family, that opting out of life can be a selfish act where you leave everyone else to pick up the pieces. Without my family, I wondered for whom I would feel responsible to keep my life. I wondered who would determine the value of my existence. I’m scared to make that determination alone.

There is a legacy of sadness and self-medication in our genes. Sometimes I wonder how our ancestors defied the odds and survived. (Was it all a Judeo-Christian “fuck you” to Darwin?)

Sophomore or Junior year of college, I was twenty, and Jackie, Jessie’s sister, drank herself to death several weeks after her divorce was finalized, the day her nephew was born; she never got to meet him. Eight years later, and I still can’t fully internalize or realize it. I can’t fathom how my aunt copes with the loss of two daughters, or how my cousins endure losing two sisters, or how little Oliver imagines the aunts he deserved, but never had. I couldn’t even conceptualize the loss of one.

Jackie was an artist with a sleeping disorder too, just like me. She was hilarious and bright. She didn’t believe in her talent and the capacity of her humor to fill often dark rooms with lightness. She dropped out of high school, and struggled through retail and food service jobs for years. Jessie and Jackie’s stories, their lives, their art, all deserve to be here more than mine.

Sometimes instead of creating my own work, I wish I was just recreating Jackie’s; channeling her spirit, finishing that dress she nearly made, because my story feels insignificant and her’s was so unjustly lost. Some art needs to be seen, mine just wants to be seen (and is kind of being a whiny bitch about it). Other times, I feel like, maybe, I am guided by her. She mostly kept her art to herself though, so do I really know her? Even if we were born with the same strawberry blonde hair, and have the same sadness etched into our bones. My mother always said, we have the same laugh.

The Graduate, An Auto-Corrected Voice-to-Text Poem From the “Notes” App

Implanted in the local system, I await apprehension. Fragility is expected but not accepted. Confront it quietly, so no one can hear. With no sniffles and hiccups ringing in my ears, perhaps there was no ringing in your ears, perhaps all sounds never happened, perhaps I was never fragile.

What really gets me is sitting on the day shift, sitting out my days—the whole world is stupid. We’ve changed. It’s a city of dives and divers. Evolution, resolution, revolution, anything goes!

I should say here that we don’t know, just by putting in pronouns, who is actually saying this. You said “mind over matter, mind over matter,” but I don’t mind so it doesn’t matter.

Dropping these words out, assorted like a ride, very slightly, so to feel more natural, great—yeah—already there’s pain, pseudo-seizures, pseudonym Caesars. This is not relieving.

Remember that dream I had where all of my teeth leapt out of my mouth? Except it wasn’t a dream, it was a memory from our childhood: I held a bloody little tooth in my hand. Excitedly, we exchanged teeth for pennies. I was told this was our right. This was the passage to beyond babyhood—our toothless grins beaming toward the future.

But now it is a dream and when I dream it, my toothless smile is eerie and unpleasant. It feels similar to falling. I wake up and I’m still falling. The cavities in your big boy teeth are deepening and so are mine.

…There’s no way to dial out. Stuck in this room I have chosen for myself over and over again, I make myself busy by yelling and trying too slowly. Oh Great Operator, can you help me place this call? Swollen with vertigo; I am all too ready to fall, tumbling toward Beethoven’s 16th string quartet, somewhere between es muss sein (it must be) and it could just as well be otherwise.